An Overview of Islam in North America

As we welcome a new decade, the last of this century, it is important that we review our performance in the ’80s.

The ’80s witnessed a large influx of immigrant Muslims to the United States and Canada. An overwhelming majority of these immigrants, both old and new, decided to make North America their permanent home. A significant increase in Muslim population also resulted from births in the community, which boasts of 6 million people in the United States and 750,000 in Canada.

The increase in population also affected the way we live and worship. Disappointed with a life without inter-community communication, proper mosques and a social support system, Muslims in the ’80s joined hands to attack these problems and made impressive gains.

While figures of the ’70s are not available, today there are an estimated 800 mosques across North America. Organizations which carry out Islamic da’wah, and social and cultural agendas of the community have been founded in every nook and cranny of the continent. While most of these organizations are rooted in the local communities, there are at least four major organizations which work on national and even continental level. The Tableegee Jama’ah, the American Muslim Mission (AMM), The Islamic Society of North America (ISNA) and The Islamic Circle of North America (ICNA), although founded before the ’80s (except ISNA), have broadened their activities and are seen as an important force in the life of the North American Muslim community.

In 1985 Warith Deen Mohammed, president of AMM, designed for African American Muslims, dismantled the organization, and asked its members to work with the mainstream Muslim community. This was a very important development, as it showed that African American Muslims had come a long way from the racist days of Elijah Muhammad, father of Warith Deen Mohammed and founder of AMM’s race-based predecessor, the Nation of Islam.

Although Mr. Mohammed and AMM did a highly commendable job in bringing non-Muslims to the fold of Islam in the ’70s, lately they seem to have slowed down. There could be two immediate reasons for this: their emphasis on indoctrinating and training members and internal divisions. Their work was also affected by a lack of rallying point for African Americans, and the Islamic Revolution in Iran. In the ’60s and ’70s, riots in black ghettos and civil rights movement had endeared Islam to many African Americans, who were looking for better alternatives to capitalism. Islam to them epitomized salvation from op pression. In the ’80s the civil rights movement, as we knew it in the ’60s, was simply not there.

In the wake of the Islamic revolution in Iran, hostage taking in the U.S. embassy in Tehran, and a spate of hijackings in the Middle East, the American media portrayed Islam in a negative light. As a result, Muslims of North America, many of whom would have proudly carried out Islamic da’wah, were forced to spend much of their time defending Islam.

In contrast with slowdown in AMM activities in the ’80s, ICNA made important gains. Founded in 1968 as an Islamic Jama’ah and movement and devoted to Urdu-speaking community until the ’70s, ICNA took its message to the entire Muslim community of North America and to non-Muslims, many of whom accepted Islam in one of its several units. It also published and distributed da’wah literature through its workers in most of the major cities of U.S. and Canada.

ICNA workers were also active in the propagation of Islam to inmates in different city jails.

However, we have a long way to go in winning the respect that we as Muslims deserve from others and fulfilling the task that we must. Despite its spiritual hollowness and liberal atmosphere, North America remains a fertile land for the propagation of Islam. And unless we change the society we have chosen to live in, it is possible the society will change us and devour our children.

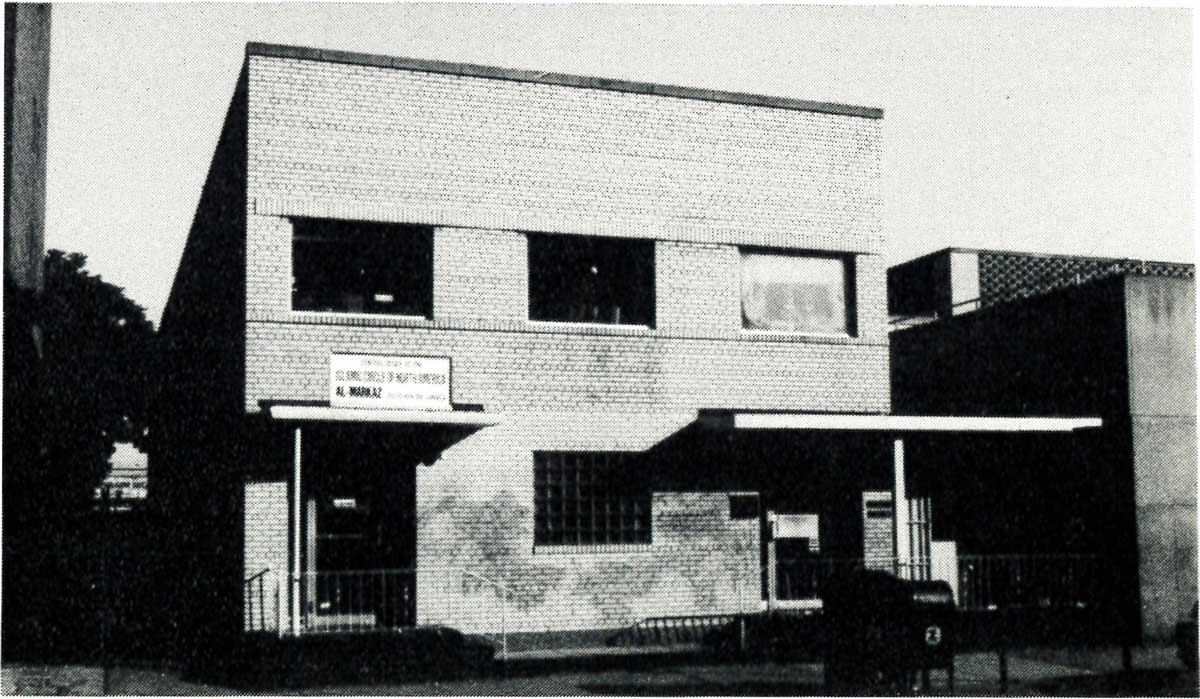

ICNA Central Office New York

ICNA central office in Queens, New York

Besides ICNA, several mosques and Islamic centers also worked towards this end. Masjid At-Taqwa and Malik Shabazz Mosque in New York City, and Masjid Al-Islam in Dallas, worked hard to rid their neighborhoods of drug dealers and invite non-Muslims to Islam. The ’80s were also important for the establishment of mosques, Islamic centers, schools, and businesses. As far as schools are concerned, the African American Muslims led the way by founding a chain of full-time schools called Sister Clara Muhammad School, in several big cities. Immigrant Muslims also made significant gains in this area. By the end of the decade, 60 schools had been established in the United States and Canada, with some of them better than many public schools. New Jersey’s Al-Ghazaly is by far the best Islamic school.

In the field of education at least three more ventures were launched in the ’80s. Among them were Is-lamia College in Chicago (1983), Nizamia Madrassah at Cornell, Canada (1985), and Darul Uloom Al-Islamiyah of America in California (1988). Unfortunately, the community response has been poor. The Islamia College, where the first batch was graduated in 1988, now has only 60 students. The two madrassahs have also had a disappointing experience. These Islamic educational institutions have to be supported by the community so that they can grow into powerful seats of learning.

To offer Muslims a chance at interest-free banking, ICNA was able to set up the Muslim Savings and Investments, Ins. (MSI) in 1985. MSI not only offers a chance to invest and earn profits, where possible, it also finances homes for qualified customers.

It is hoped that in the ’90s MSI will develop into a full-fledged bank.

There are many financial institutions which were established in ’80s. Some are interest-free like Baitul Maal (BMI) of New Jersey, and some have investment in stocks (according to many `Ulama is not halal) like Amana Mutual Funds.

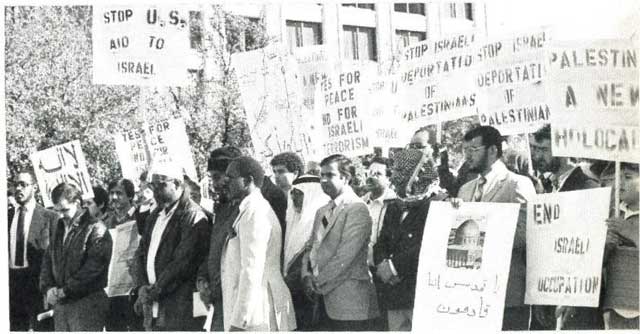

In the area of housing Toronto Housing Coop, in Canada, was an important Muslim organization to be founded in the ’80s. Started by a few sincere Muslims, it has been able to buy more than 100 interest-free homes for the community. Other smaller organizations are also working in other cities on these lines. The ’80s also saw a growing unity and sense of Ummah among Muslims of North America, both indigenous and immigrant. The unity was reflected in the community’s work in providing political and monetary support to jihad in Afghanistan and Palestine. A number of Muslims were so dedicated that they actually went to Afghanistan to fight against the Communists.

Unlike the ’70s, Muslims in the ’80s showed political awareness and began taking active interest in the mainstream political parties of the United States and Canada, with some of them holding political offices. Muslims played an important role in the election of (late) Chicago Mayor Harold Washington, Detroit’s Coleman Young and Virginia’s governor L. Douglas Wilder. It is noteworthy that in Detroit a Muslim, Adam Shakoor, was chosen as the deputy mayor. In the 1988 presidential elections, Muslims got involved in the campaigning and as a result were able to push their weight behind Rev. Jesse Jackson’s debate of the Palestinian problem on the Democratic Party platform. First time in the history of U.S., the Senate has passed a bill (S.794) in 1988 which also includes Muslim and Mosque. This legislation makes it a federal offense to interfere with the exercise of religious freedom, or to damage or desecrate religious property. In the ’80s Muslims learned that American politics was governed by interest and pressure groups. The first significant manifestation of this realization was the founding of the Muslim Political Action Committee (MPAC) in California. Similar efforts have been made in New York and Illinois. ISNA held a conference in 1989 in this context, and it determined to mobilize people towards greater participation in political process of North America.

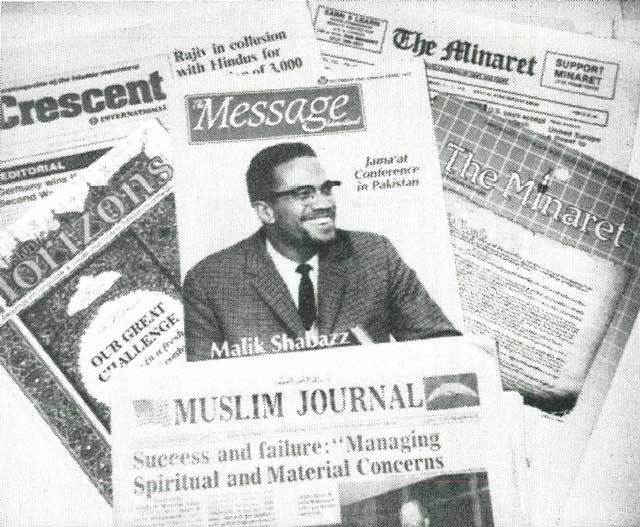

Major Islamic magazines and newspapers of U.S. and Canada

The role of the mainstream American media in the ’80s continued to be hostile and negative towards Muslims. However, there was a realization that unless Muslims worked on this area, they would have to be always defensive. The Rushdie affair drove this point home very powerfully and helped galvanize Muslim activism. At the end of 1988, ICNA took up this matter on a continental basis, and along with different Islamic centers and Muslim organizations, tried to have Salman Rushdie’s book “The Satanic Verses” banned. Although Muslims were not successful in getting the book banned, the outrage over it brought them together and gave them a chance to talk to the media and present their side of the story. It was also the first time that many non-Muslims learned about Muslims and their religion so extensively.

The Rushdie affair also opened doors of inter-faith dialogues, arranged until the early ’80s mainly by Muslim Students Association, a little wider. Now Christian organizations began to invite Muslims for interfaith dialogues and included Muslims in several committees dealing with interfaith matters. However, much needs to be done. Muslims should try to gain a place on the boards of public television networks where major religions are represented. They should also invite the media to their functions and programs so that Americans can know them better.

Speaking of the media, Muslims in the ’80s made progress in this direction. Many Islamic centers began to publish a monthly or quarterly magazine to air their point of view and publicize community issues. Important among the many are the weekly Muslim Journal (Chicago), bimonthly Islamic Horizons (Indiana), tri-monthly Minaret (California), biweekly Minaret (New York), Crescent (Toronto) and monthly The Message International. Among the Islamic publications, The Message is an up-and-coming monthly international magazine and fills the void created by the closures of the London-based Arabia and Afkar.

Like the ’70s, Muslims did not have much involvement in the electronic media in the ’80s. However, paid Islamic and non-Islamic cultural programs continued to be aired on local channels. In this regard the role of the California-based Islamic Information Service (IIS) is important. A major problem with some ITS programs is that they have not portrayed Islam properly. This has to be corrected if we are to save Islam from ridicule and ideological impurities. TV is the most effective news medium and Muslims should increase their presence on it, and also see that Islam is not presented in a twisted manner.

In the ’80s the Muslim community, reflecting greater maturity, entered hitherto unchartered waters. Although not all its new initiatives succeeded, at least they decreased its insularity. For instance, in the early ’80s ISNA experimented with the Muslim Community Association (MCA), an organization designed to unite the communities. Due to several reasons MCA failed and had to be scrapped. Perhaps the main reason of its failure was that it was not a grassroots organization and had not involved the entire community in decision making.

Realizing that a whole new generation of Muslims had come of age, both ISNA and ICNA separately founded youth organizations that are called Muslim Youth of North America (MYNA) and Young Muslims for Faith and Action (YMFA). While MYNA is basically concerned with organizing summer camps for youths, YMFA is based in different towns and cities where Muslim youths organize into groups and carry out Islamic and extracurricular activities. Muslim youths are our invaluable asset for the future, and if they are not cultivated Islamically, we would lose them to the American society, just like the early Muslim settlers did. We need to mobilize ourselves and the community, and act now!

The ’80s also saw the establishment or expansion of several research and publishing organizations. The most notable among them are the Virginia-based International Institute of Islamic Thought and American Trust Publication, and Vermont-based Amana Books. The ATP and Amana, which are basically Muslim publishing houses, have produced some very useful books. But they have not been able to fulfill the needs of the entire community, nor publish much-needed books for youths and Islamic education. In the ’90s we definitely need more books of this kind. We also need more Muslim intellectuals and activists to deal with social, academic and religious problems faced by the community. In this context, ICNA has decided to form an Institute of Leadership Development to train Muslims to handle the responsibilities of imam, directorship of an Islamic center and da’wah work.

In the area of ibadah, or worship, Muslims were found lacking in the ’80s. Although there has been an impressive increase in Muslim population and mosques in the last decade, no more than 10 percent of Muslims living in the vicinity of a mosque attended Jum’a prayers. This is particularly disheartening to those da’wah groups and activists who worked hard to bring Muslims to the house of Allah. The lack of attendance even in Jum ‘a prayers is not a healthy sign, and the problem must be corrected. On the other hand, those who did come to the mosque, were only concerned with offering prayers. Most of them made no effort to pass the message of Islam to their neighbors. ICNA has started preparing Muslim Data Base to reach to these 90% Muslims who are not involved in any Islamic activity. At the end of ’80s thousands of names and addresses of Muslims have been computerized.

No one can deny the modern Western civilization’s productivity, comfort and affluence but it must be regrettably acknowledged that Western civilization’s shortcomings and weaknesses are no fewer than its advantages. Despite the leisure and ease which American science and technology provide for society and despite the new pages of history turned, human happiness has not increased nor have social ills diminished. Living and bringing up of new generation in this non-Islamic society is a great challenge for Muslims.

Despite many gains and lot of Islamic work, like the ’70s, many Muslims in the ’80s were not successful in meeting this great challenge.

Indigenous and immigrant Muslims united in a rally in Dallas, against Israeli occupation of Palestine

In some cases, the whole Muslim family lost the Islamic and Muslim identity and accepted the American and secular norms and ideology and even they changed their names from Muhammad to Mo, Sulaiman to Sam and so on. The world has tried all the religions and ideologies whether it was Hinduism or Socialism, Communism or Capitalism, none gave the humanity the peace of heart and mind. But Islam is the only way of life which can cure the mankind from their diseases, can provide the peace of heart and mind in this world and success and falah in the hereafter. The Muslim community will have a bright future in the ’90s and beyond if it can come into the fold of Islam completely and totally. And show a greater desire for pan-Islamism and pool its resources towards the creation of a United Islamic Movement consisting of workers of Islamic movements and movement-oriented indigenous brothers and sisters of the U.S. and Canada. This is the most important requirement if we want to preserve ourselves as Muslims.

Just preservation is not the guaranty for success. Therefore, Muslims have to propagate the message of Islam (da’wah) to fellow human beings. Da’wah is a comprehensive program which includes every aspect of Islam. A Muslim as an individual and the ummah as a collective body cannot absolve itself of its responsibility of da’wah if it is not an all-embracing movement. And this da’wah has to be relevant to North American society.

Then we hope through the ’90s and beyond that the future will belong to Islam and America will belong to Islam, In shaa Allah.