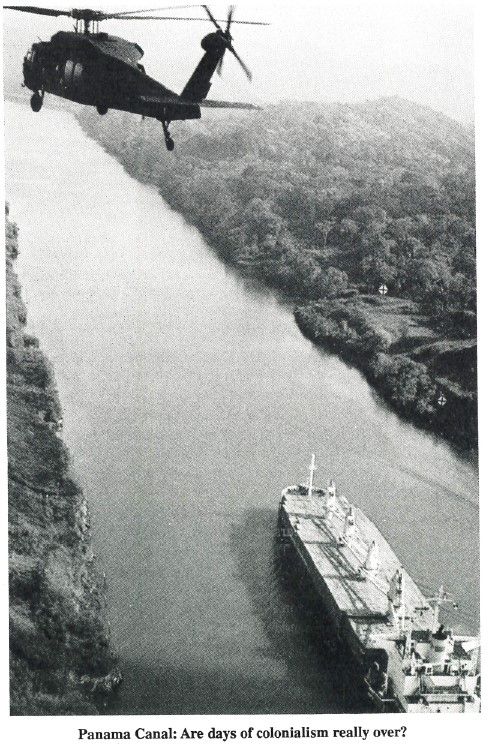

The history of Panama amazingly repeats itself. Panama has for long been a victim of the United States jingoistic foreign policy. Three major factors have dictated U.S. policy towards Panama race, economics and politics. The recent invasion of Panama brings the number of ‘U.S. military intervention in a foreign country in this century to 11. All but one – the 1958 U.S. intervention in Lebanese civil war – occurred in the Caribbean or Central America. In an article titled “A New U.S. Willingness to Use Force?” in The Washington Post (January 5, 1990), John M. Goshko and Al Kamen have pointed out that some U.S. specialists on Latin America agree that the U.S. stake in the Panama Canal and its adjacent bases was the prerequisite for the invasion. They say it has been politically pragmatic (beginning with ‘Theodore Roosevelt) for the U.S. to dispose of a disliked leader who threatens ‘U.S. economic and political interests. Theodore Roosevelt utilized the Monroe Doctrine to command a U.S. Cavalry regiment in Cuba during the 1898 Spanish-American War. In 1903, he sent warships to ensure that the U.S. backed establishment of an independent country called Panama would be ensured, along with the new Panamanian government’s agreement that the United States could build a canal there.

In 1823 when Central Americans revolted against Spanish rule, Panama joined Columbia which already had declared its independence. For the next 82 years the country struggled unsuccessfully to end its status as a vassal of Colombia. That colonial lasted until 1903. Panama differs from other Central American states in that it has always been a region where the mass of the people had a varying degree of African connection. In his informative and seminal work titled The African Experience in Spanish America – 1502 to the Present Day, Dr. Leslie Rout, Jr. says that of the 35,920 people in the Province of Panama in 1789, 22,504 (about 63 percent) were either slaves or free Negroes. In the years following independence, political changes often transpired, but they were never powerful to root out antagonisms of color or caste. Race wars flared up in Panama City and Colon during the 1830’s eventually Caucasians prevailed.

Although people of African heritage constitute a majority in Panama, it is the Caucasians who have always dominated the country. This Caucasian element has consciously maintained its so-called racial purity. Thus, the construction of the canal was the basis of the tripartite dispute.

Panama declared its independence from Colombia on November 6, 1903, and was aided in this by the United States which had its own ulterior motives, Subsequently, the Hay-Banau Varilla Treaty was signed the following year granting the United States rights for the inter-ocean canal and virtual political sovereignty over a zone five miles on either side of the project route. Panama is the southernmost Central American country. It is a country with volcanic mountains in the West and rain forests in the fertile eastern region. Most of Panama’s population is close to the canal. The canal bisects the Isthmus, which connects North and South America, at its narrowest and lowest point, allowing passage between the Caribbean and the Pacific Ocean.

The law firm of Sullivan Cromwell and the Baig family (who played the single largest role in the development of Latin America) were instrumental in negotiating the purchase of the Central America rights for the building of the Panama Canal. Construction of the canal began in 1904, and since there was a shortage of manpower, the United States brought in Spaniards, Italians, and 44,000 laborers from Barbados, Trinidad, and Jamaica. The North Americans who came to Panama were, for the most part, skilled technicians and engineers. As an incentive, those workers were paid in gold and were referred to as “gold employees;” the manual laborers were referred to as “silver employees.” Needless to say, the Italian and Spanish laborers received considerably better pay than the Panamanians or the West Indians. The work environment for silver employees was so harsh that thousands of these West Indian blacks died of malnutrition, disease and severe exhaustion.

The law firm of Sullivan Cromwell and the Baig family (who played the single largest role in the development of Latin America) were instrumental in negotiating the purchase of the Central America rights for the building of the Panama Canal. Construction of the canal began in 1904, and since there was a shortage of manpower, the United States brought in Spaniards, Italians, and 44,000 laborers from Barbados, Trinidad, and Jamaica. The North Americans who came to Panama were, for the most part, skilled technicians and engineers. As an incentive, those workers were paid in gold and were referred to as “gold employees;” the manual laborers were referred to as “silver employees.” Needless to say, the Italian and Spanish laborers received considerably better pay than the Panamanians or the West Indians. The work environment for silver employees was so harsh that thousands of these West Indian blacks died of malnutrition, disease and severe exhaustion.

The United States, which viewed the Panamanians and the West Indians as inferiors, recruited supervisors for them from the segregated south. This was done in the belief that southerners “knew how to deal with Negroes best.” The segregated system that was legal throughout the southern United States was in part transferred to Panama. As a result, racial tensions between Panamanians and West Indians intensified. Needless to say, the white Panamanians held sway in the region. The West Indian blacks refused to as simulate into Panamanian culture and there was an effort headed by the U.S. to send them elsewhere, but they were needed to defend the canal against the German Nazis and Japanese. Time, unfortunately, did not erase the barriers that West Indian blacks and even Hispanicized Panamanian blacks faced from white Panamanians.

After the Spanish-American War, the U.S. control of Puerto Rico and the Philippines and established a protectorate over Cuba. The ‘U.S. had become an imperialist power with semi-colonies in two oceans and therefore needed a canal to shorten the travel time between the East and West coasts of the United States. The canal placed the U.S. in a competitive position in world trade and commerce and bolstered its military position.

The United States Senate ratified the canal treaty on February 24, 1904, which allowed the U.S. army to intervene in Panama beyond the canal zone if necessary. The U.S. paid Panama for canal rights for 100 years.

The United States jurisdiction covers some 553 square miles of Panamanian land. Of this, only about 3 percent of the land is actually occupied by the canal, while 68 percent is taken up by American military bases and reservations. From its control of the canal during World War II, the U.S. reaped huge benefits. According to information presented to the U.S. Congress by the canal zone governor in 1947, “monetary saving to the United States arising from the use of canal is estimated at $1.5 million in maritime costs alone without consideration of the lives and materials that were saved.”

One little told fact about the recent U.S. invasion of Panama is that on January 1, 1990, a week before the military intervention, the administration of the canal was to go into the hands of a Panamanians, under provisions of the canal treaties signed by then U.S. President James Carter and Panamanian leader Omar Torrijos in 1977. This treaty was supposed to relinquish U.S. control of the Panama Canal to Panamabytheyear2000. The Carter Torrijos treaty stipulated that total control of the canal and administration would go to Panama also the American military bases which number 13 – would be dismantled. Hence these treaties replaced the Panama Canal Co. That was exclusively under U.S. control. A nine-member commission (five from the U.S. and four from Panama) was established to usher in the transition. The commission, which was supposed to be headed by a Panamanian chief administrator, would grant full operation of the canal zone to Panama, and dismantle the U.S. military bases in the canal by the year 2000.

Within 10 years, it became apparent that the United States did not really want to honor the 1977 agreements. Various sectors of the U.S. ruling class voiced their opposition to this impending transition. The strategic military role of the canal, the U.S. military bases in the canal zone, and the annual multimillion dollar revenues were too important to give up without resistance.

Mr. Noriega came to power in 1983. This occurred three years 4ter the mysterious death of Mr. Torrijos. The new leader assumed control of the National Guard, which he renamed Panamanian Defense Forces. Around this time Washington’s “Contra” war against the Nicaraguan Sandinistas was in progress, and the U.S. Southern Command was poised to participate from its station in the canal zone. Much to the chagrin of Washington, ‘ the Noriega regime called for an end to the war and openly opposed deepening U.S. military intervention.

By 1985 the Sandinistas had gained significant military ground. The Contras were weakened. John M. Poindexter, the national security ad visor at the time, visited Mr. Noriega in 1985 to demand that Panama Defense Forces directly aid the Contras. Mr. Noriega refused. Soon a campaign began in Congress denouncing him as a double agent, which connected him to the CIA and the Cuban intelligence at the same time. Several months later, charges of drug smuggling were also leveled at Mr. Noriega.

In a desperate move, Washington turned toward a former Panamanian ruling class known as the Rabiblancos (which has a vulgar meaning); this group represents wealth, ties to the U.S. government and is considered of white race. These people joined hands to establish a “Civic Crusade” in 1987 and demanded that Mr. Noriega relinquish power. Mr. Noriega charged that he was being pressured, to some extent, because of domestic racism. This group organized strikes, rallies, and other kinds of demonstrations against Noriega. It worked closely with the U.S. Despite what the Panamanians thought about the Noriega government, one thing that was clear was their contempt for the Civic Crusade. They even mockingly referred to members of the crusade as the “Mercedes Benz” people because they usually came to rallies in the latest models. Nevertheless, they eventually lost momentum in their attempt to overthrow Noriega.

Washington panicked, as a result developed a plan that was geared toward shattering the Panamanian economy. The events unfolded when the U.S. imposed economic sanctions against Panama, thereby making life miserable for the masses. The U.S. froze $56 million in U.S> banks and cut off aid to Panama.

With success still elusive, the United Staves finally invaded Panama and installed a leader favorable to the U.S. The American democracy was showing its ugly side. While Washington has removed Mr. Noriega saying he was a dictator and drug dealer; it has supported such dictators as General Augusto Pinochet of Chili, the late Ferdinand Marcos of the Philippines, the late Shah of Iran, Papa Doc and his son Baby Doc of Haiti, and the late Samoza of Nicaragua. And most recently it practically condoned the massacre of Chinese students by the Marxist government in Beijing.