“The language of Zanzibar par excellence is Swahili, and Zanzibar may be said to be the home of this language. After the days of opening up of Africa, explorers (Missionaries) and traders (Orientalists) generally fixed up their caravans in Zanzibar, and these porters (Colonialists) and soldiers (Crusaders) journeyed into the exterior, some of them remained there and thus making Swahili a lingua franca understood.”

Source: W. H. Ingram (1923). “The Dialects of Zanzibar” Bulletin of school of oriental studies. Vol. 11. p.1

0ne of the unique features of the Swahili language is that it has had a written tradition since the (late) sixth century. The Qur’anic script was used by the Waswahili, a generic lingo-ethnic identity of the people along the East Coast of Africa, stretching from northern Mozambique to Kismayu in southern Somalia. It was later used extensively in poetry.

However, it was only in 1924, after the Anglo-Dutch Colonialism in the East African countries, that the Roman script was introduced by the Orientalists and Christian Missionaries. Although the Roman script is widespread, the Qur’anic script is still used in personal documents. The effect of British Colonialism on the Zanzibar Swahili has been to cleanse its Qur’anic impact for secularization, ostensibly in the name of standardization (Christianization) of the Zanzibar Swahili. The ultimate goal is to totally destroy the Islamic culture in Zanzibar, the last stronghold of Islam in East Africa. as Cordova in Spain.

Although the Zanzibar Swahili developed as an Islamic language, it has increasingly become the heritage of Africa as a whole. Truly, the impact of Qur’anic loan words is irreversible as the impact of Latin on the English language. But the Standard Swahili is becoming less Islamic and more African due to its Ecumenism for Christianization in East Africa and beyond.

Generally, two trends have made the Standard Swahili less Islamic. First, Christian missionaries and Orientalists in Zanzibar used Swahili as a medium of worship and theology for spreading Christianity. Swahili Islamic concepts were intended for Muslim discourse penetrated into the vocabulary of the Bible and African paganism. This crucial trend of Zanzibar Swahili is a part and parcel of its ecumenicalization from church state to marketplace.

The second trend is the secularization of Zanzibar Swahili. This involved the increasing use of Swahili in areas of African life which are no longer as deeply affected by religion as they once were. The Zanzibar Swahili was so powerful that it was the most important instrument of social and economic development from Barawa, Somalia in the north to Sofala, Mozambique in the south along the East African coast. The need in secularization of the Zanzibar Swahili has encompassed its use for the administrative, economic and political purposes.

As for the impact of Anglo-Dutch Colonialism on the Zanzibar Swahili, this has been a process of contradictions. This Colonialism arrested the spread of the Swahili Islamic language, but fostered the spread of the Zanzibar Swahili, which Professor Ali Mazrui and Pio Zirimu called an “Afro-Islamic” language.

According to them, the Islamic civilization has suffered, but the linguistic side of the Islamic civilization gained. They argued that both the Germans and the British contributed to the triumph of the Zanzibar Swahili as a lingua franca in East Africa. On the other hand, the Christian missionaries promoted Christianity and constrained the expansion of Islam. Ironically, they often used the “Afro-Islamic” language to spread the Gospel of Jesus in the East African countries before and after their respective independences.

Spread of the Zanzibar Swahili before independence

UGANDA: Paradoxically, Swahili was the first non-Ugandan language to be used in that country. Both oral and written Swahili was already in use in the courts of the kings of Baganda and Bunyoro before the first British set foot in Uganda for Christianization. Even Bishop A. Mackay, who frequently evangelized Kabaka (King) Mutesa (1856-1884) of Uganda agreed that Swahili should be used for spreading Christianity:

“Fortunately, Swahili is widely understood, and I am pretty much at home in that tongue, while I have many portions of the Old and New Testaments in Swahili. I am thus able to read frequently to the King of (Uganda) and the whole court (of Buganda) the word of God.”

Earlier, the Muslims from Zanzibar had already introduced Swahili in Uganda through Islamization. Despite the fact that the British used the Zanzibar Swahili to impose Christianity under Colonialism in Uganda, the hired Orientalists and Christian Missionaries opposed Swahili for two main reasons. First, in order for the spread of Christianity to be well understood by Ugandans, it had to be taught in the mother tongue, and since Swahili did not belong to any indigenous tribal group in the country, it could not serve that purpose.

Their second reason was based on Islamophobia. One of the strongest opponents of Swahili in those days was Bishop Tucker. He lamented that “Swahili is too closely related to Mohammedanism (sic) to be welcomed in any mission in Central Africa.” The Christian Missionaries promoted the indigenous languages of Uganda which, over the years, became very ingrained for Swahili to compete with. An important note here is that the Christian Missionaries discarded Swahili after acquiring a grasp of Luganda, one of the languages of Uganda. In the words of Bishop Tucker:

“(Bishop A.) Mackay…was very desirous of hastening the time when one language should dominate Central Africa and that language, he hoped and believed, would be Swahili…That there should be one language for Central Africa is a consummation devoutly to be wished, but God forbid that it should be Swahili. English?! But Swahili never! The one means the Bible and Protestant Christianity—the other Muhammedanism (sic)… sensuality, moral and physical; degradation and ruin…Swahili is too closely related to Muhammedanism (sic) to be welcome in any mission field in Central Africa.”

In 1927, the Governor of Uganda, Sir W. F. Gowers recommended that Swahili be widely used as an educational and administrative language of the country, instead of English and Luganda. This suggestion prompted the Baganda to unite with the Christian Missionaries in opposing Swahili and insisted that the Luganda should be used instead. The opposition of the Baganda was implied in a statement made by the Kabaka (King) of Baganda, Sir Daudi Chwa in 1929. He opposed Gower’s recommendation because the Baganda might lose their national identity.

In spite of the establishment in 1930 of an Interterritorial (Swahili) Language Committee, the Ugandan Bishops, both Protestant and Roman Catholic, submitted a weighty memorandum to the Colonial Secretary in London through the Governor of Uganda. The burden of the memorandum was to demolish the arguments for Swahili as the official language and put a strong case for Luganda.

Nevertheless, Swahili remained a suitable medium of instruction in police training institutions, prisons and armed forces. This concerted opposition to Swahili not only proved to be the death of this language locally, but also spelt danger to the native language of Uganda as well. Because in 1953 the Royal Commission of East Africa ruled out the teaching and official usage of Luganda, to make way for English.

TANGANYIKA: Events in Tanganyika were different from those in Uganda. Tanganyika was first ruled by Germans. There were two main factors for spreading Swahili in Tanganyika. First, Islamization by Zanzibari Muslims, after the settlement of Sayyid Said bin Sultan (1806-1856) to Zanzibar, Swahili had emerged as a lingua franca. The Germans took advantage of this consolidated language by using it in schools and administrations. Like the British in Uganda, the Germans in Tanganyika used Swahili to govern and spread Christianity. The second factor which increased the prestige of this language was the German government’s policy of making Swahili compulsory for German officers before they were dispatched to Tanganyika.

German Christian Missionaries learnt the Zanzibar Swahili before they arrived in Tanganyika. Though by 1914, most of the German administrators carried out correspondence in Swahili, they did not take this step for the nostalgia of the language. The people used it, but only to facilitate their Colonialism in Tanganyikan. Because the reasons given by the German themselves for their decision was that “it is better and wise politically not to teach the African German because by doing so we will be opening our secret to him.” The German Missionaries were highly Swahiliphobic because Swahili is irredeemably mixed with Islam and must be obstructed. Marcia Wright (1971) stated in Germans Mission In Tanganyika that:

“In Germany, Director Buchner proved to be unrelenting for Swahili, going so far in a speech before the Kolonialrat in 1905 as to declare that it was so irredeemably mixed with Islam that every expedient ought to be employed to obstruct their joint penetration….Buchner’s opposition to Swahili was adopted and expanded by (the Rev.) Julius Richter, a member of the Berlin Committee. The Rev. Richter delivered a diatribe during the Kolonial Kongress in 1905 against the pernicious influence of Islam everywhere in Africa. Isolating East Africa as the scene of the worst danger, he envisage a mosque alongside every coastman’s hut, and took the official support for Swahili to be blatantly pro-Islamic.”

After the defeat of the Germans in the First World War (1914 -1918), Tanganyika, was colonized by the British. The new Colonialists found that Swahili had already been established in the administration and in the educational system. In 1925, besides the Zanzibar Swahili, the British Missionaries introduced vernacular languages in the lower primary classes, but Swahili in the middle ones, and English in the upper level. Because of the development of the Swahili during German Colonialism (1885-1918), this change of policy regarding the medium of instruction in the educational system had little effect on Swahili. This was due to the fact that in most parts of the country, the trend was irreversible. By 1945, the vernaculars had also disappeared from the school system.

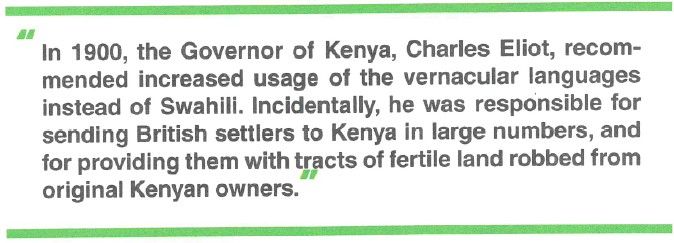

KENYA: As was the case in Tanganyika, Swahili was well established in Kenya before the penetration of the British. But in Kenya, the British started to undermine and suppress Swahili immediately after hosting their flag of the Union Jack. Also, the Christian Missionaries did not wait so long before advocating the use of vernaculars for two reasons. First, it was easier to read a person’s mind through one’s knowledge of the mother tongue. Second, it Was easier to impart knowledge to a pupil by using his vernacular. To some of the Christian Missionaries, their strong opposition to Zanzibar Swahili stemmed from the fact that it incorporated many words of Arabic origin containing Islamic concepts.

In 1900, the Governor of Kenya, Charles Eliot, recommended increased usage of the vernacular languages instead of Swahili. Incidentally, he was responsible for sending British settlers to Kenya in large numbers, and for providing them with tracts of fertile land robbed from original Kenyan owners. These settlers were not only against the Kenyans learning English, but also not interested in learning proper Swahili. As a matter of fact, they despised and regarded it with contempt. They considered it useful only when “giving order to (Kenyan) servants.” Swahili was therefore called “Kisetla” meaning the language of the settlers. This, to a certain extent, caused Kenyans in those ares to oppose and despise Swahili, for they associated it with low status.

One of the settlers, Major E.S. Grogan, when making his contribution to the debate in Kenyan Legislative Council on 18 October 1929, said that: “I cannot think of anything more dangerous than teaching English to Africans. The only good education for them is to work as labourer on the farm.” Despite this the East African Royal Commission (1953-1955), under pressure from the Christian Missionaries conducted in a report that to teach and treat Swahili as the second language, was a complete waste of time and effort.

By 1958, many Kenyan schools in the rural areas abolished the teaching of Swahili and concentrated on English. They were made to believe that English was a language of prosperity and civilization. The Kenyans were led to expect to reap material benefits by adhering to this new policy as the editorial of the daily, East African Standard (renamed The Standard) reported that:

“If mothers of tomorrow could bring up their children with English in home, progress would be swifter and surer.” (13 May 1960).

Spread of the Zanzibar Swahili after independence

UGANDA: When independence was imminent, the Ugandan People’s Congress (UPC), led by Milton Obote, agreed to start giving Swahili national status in the country, and delegates at the UPC Conference in 1961 passed a resolution that Swahili be taught in Ugandan schools. However, after independence, this was not pursued. This may be attributed to the fact that the first Ugandan government was a coalition between the UPC and the predominantly Baganda monarchist party called “Kabaka Yekka” which was led by King Edward Mutesa.

Therefore, English continued to be the official language and the medium of instruction in independent Uganda, as it was under the British Colonialism. In addition, the vernaculars were encouraged as regional and tribal languages. Nearly 20 vernacular languages were broadcast by Radio Uganda, but English as the main language on radio and television. The following statement made in 1967 by the Attorney General of Uganda reflected the official attitude on Swahili:

“The Official language of the Government of Uganda shall be English…Swahili is no near to the language of honorable member than Gujerati….He might as well learn what they speak in Paraguay as learn Swahili.”

During the reign of Idi Amin Dada (1971-1979), for the first time in the history of Uganda, Swahili was given national prominence. It was used in the national services of both Ugandan radio and television. He stressed the significance of Swahili from a Pan-African context when he addressed his nation:

“On the advice of the entire people of Uganda, it has been decided that the National Language (of Uganda) shall be Swahili. As you all know, Swahili is the lingua franca of East Africa, and it is a unifying factor in our quest for total unity in Africa.”

In 1979, this first post-colonial Muslim President, Idi Amin Dada, was toppled by the first post-colonial Catholic President, Julius Kambarage Nyerere. He installed Dr. Yusuf Lule, his schoolmate at the University of Edinburgh. Many of the Nyerere’s soldiers who participated in his Catholic Crusade, branded as vita vya Kagera, were ironically Muslims, many among them from Zanzibar. Their reward by Nyerere was nothing but many Ahsante!!! (thanks)

They, and some Ugandans who had exiled in Tanganyika, helped to promote Swahili, and bestowed on it the honor it had never had. Swahili is now being taught at the Makerere University in Kampala, Uganda, something which was never dreamt of during Milton Obote’s first phase in power (1961¬1971). At present, there is no clear language policy in Uganda regarding Swahili as opposed to Tanganyika.

TANGANYIKA: Despite the impact of Qur’anic language in the Zanzibar Swahili, when Tanganyika became independent in 1961, moves were already underway for realizing the dream of making Swahili the national and political language. This was made essential for the benefit of Nyerere to gain Union support of Muslims from Zanzibar.

Most of the Zanzibar representatives in the neo-Tanganyikan parliament did not understand English. Others did not know languages of their counterparts in Tanganyika. To the Zan-zibaris, Swahili is their only indigenous language. Because the language is power, the National Kiswahili Council of Tanzania (Tanganyika) was formed by an act of Union parliament in 1967, and was entrusted with the work of overseeing, directing, encouraging and developing Swahili.

However, we can argue that the formation of the National Kiswahili Council of Tanzania was a rubber-stamp of Inter-Territorial (Swahili) Language Committee (ITLC) for a continuation of standardization of Zanzibar (Christianization) Swahili from primary education to the National Executive Com-mittee (NEC) of the ruling Chama Cha Mapinduzi.

In the educational system, the medium of instruction in all primary schools is Swahili, while in secondary schools only some subjects are taught in Swahili. Currently, the educational institutions are trying to overcome the handicap of teaching science in English by preparing the required scientific terminologies, books and dictionaries in Swahili. At the University of Dar es Salaam, a higher degree can be pursued in the Swahili language.

KENYA: In Kenya, there are many educated Kenyans who feel proud that they understand no language, even their own mother tongue, better than English. Such people do not take Swahili seriously, but regard it as the language of the uneducated. In 1964, the government declared Swahili the national language of Kenya. After the announcement, no steps were taken to implement the decision. In 1974, President Jomo Kenyatta (1963-1979) ordered the parliamentary procedures to be held in Swahili and English instead of English alone. Very few members chose to speak Swahili, though by law, to be eligible to stand for parliamentary election, a candidate must pass a language proficiency test in both Swahili and English.

The policy of the Swahili language in Kenya is confusing, but legally, English is the official language. Of the two, it is English which is being emphasized in offices. But in primary schools, it is a compulsory language, and the medium of instruction while in secondary schools. Swahili is an optional language, and because of this lack of emphasis, most Kenyan students prefer to learn French, German or Latin. Although Swahili is one of the 15 vernacular languages in broadcasting on national services, no other language is as widely used in Kenya today.