Nineties Seem Promising, but Efforts Are Needed

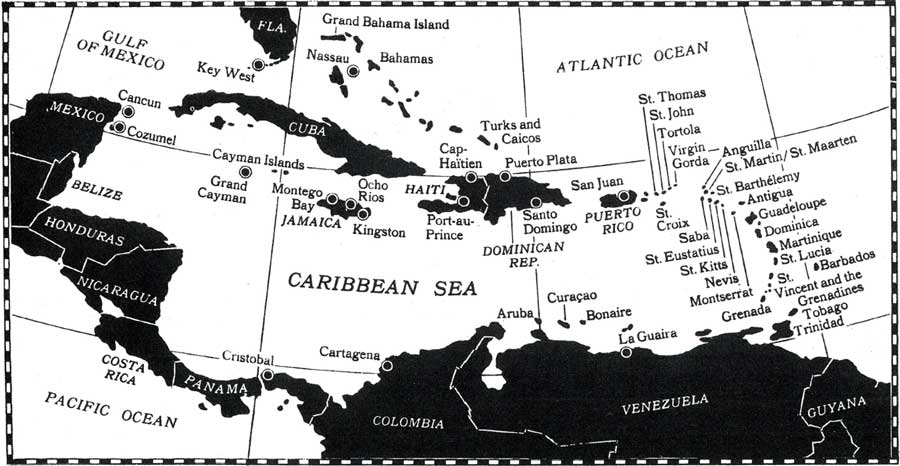

The history of Islam and the presence of Muslims in the Caribbean has been a very unique experience which needs to be adequately researched. It stretches back over one thousand years, predating European contact by over six centuries. Long before the voyages of Columbus in the 15th century, Muslims from North and West Africa, visited, settled and established a viable trade and social relationship with American Indian people. A number of sculptures, oral traditions, eye witness reports, artifacts and inscriptions have been sighted to confirm this. (Imam Abdullah Hakim of Toronto, Canada, presented a well researched paper on topic at the International Islamic Conference in Nigeria last November.)

The second presence of Muslims were slaves, kidnapped by or purchased by European slave traders and transported from West Africa to a ‘New World’ of oppression and inhumanity. Over a period of 300 years, millions of slaves were transported in what must be one of the most barbarous episodes in human history. The fact that many of these slaves were Muslims is beyond doubt. Many of them came from the predominantly Muslim African ‘nations’ such as the Mandin, the Fula, the Susn and the Hansa, and there are indications that some of them were distinguished scholars of Islam.

Despite slavery and forced separation from Islamic lands and culture, there are reports of Muslim slaves maintaining a form of their faith, leading slave revolts and in some cases regaining their freedom and returning t o Africa. The leading force among the Muslim African slaves were the Madinka, known in the Americas as “Mandingo.” They were found in considerable numbers in Jamaica, Trinidad, St. Vincent, Venezuela and other Caribbean nations. Many historical reports on this incredible period are now available.

Between 1838 and 1924, a new element was introduced through the process of indentureship into the Caribbean population. Nearly half a million ‘East Indians,’ as they were called, entered the region, mainly in Guyana, Trinidad and Surinam and also in Guadeloupe, Martinique, Jamaica, St. Lucia, St. Vincent, and Grenada. One in six, were Muslims, the rest Hindus. The Dutch introduced these workers from the Netherland Indies (mainly Java) who were mostly Muslims and were settled in Surinam.

The ‘Indian’ Muslims had come primarily from the illiterate class and were forced to coexist with the Hindus. The living conditions were very similar to that of the slaves and they were severely abused and exploited. They were not able to adequately transport Islamic com munity life and they became the target of hostility from every angle. As a result of this atmosphere of hostility they reacted by becoming very introverted and inward looking. Preservation of the self became the main objective for them and little or no efforts were made to propagate Islam. However, they were able to establish mosques in many communities in Trinidad, Guyana, Surinam and Jamaica around which some aspects of community existence were achieved primarily from 1865 into the first half of this century.

This period at least resulted in a sustained presence of Muslims in the Caribbean and laid the basis on which Islamic reawakening has taken root today.

Achievement in the Eighties

The ’80s can be considered a decade of sober reflection, realism and maturity. After the spontaneous injections of Islamic reawakening throughout the Caribbean in the seventies, Muslims and their communities began to settle into their own development. The sudden growth of Islam and the bombardment of external forces began to subside. This left community time to reflect on their level of development.

The sincere and dedicated efforts to forge an indigenous movement blossomed as the only viable mechanism to tackle the diverse problems of building Muslim communities in the region. The Association of Islamic Com munities of the Caribbean and Latin America (AICCLA) undertook this challenge by initially focusing on the educational and training needs of the communities. Islamic studies and da’wah were offered in every community based on common grounds. A series of three day ‘in-house’ community programs were con ducted zeroing in on the needs of each community. These programs, involving all Muslims in their communities, were implemented in Grenada, Barbados, Dominica, Jamaica, Bahamas and Belize from 1980-85.

Similarly, in Trinidad and Guyana national conventions were organized by the Islamic Da’wah Movement, (IDM) and the Guyana Islamic Trust (GIT). These highlighted the persistent efforts to rejuvenate the existing Muslim communities by organizing classes, study-circles, seminars, training camps and community involvement in mosques and centers throughout their respective countries. Despite the fact that Guyana is the second poorest country in the region (after Haiti), the GIT has been able to conduct its training programs every year in the towns and villages of Guyana. These selfless youths were able to travel the length and breadth of the country (hundreds of miles) and even develop parallel programs for young women! They also succeeded in spreading Islam to the African population. Today, their members are serving as Imams and leaders throughout the country.

In Trinidad, the workers of the Islamic Trust, reorganized themselves and in 1985 founded the Islamic Da’wah Movement. Many of these workers rose to influential positions in mosques and dormant Muslim organizations. A number of kindergarten schools for Muslim children were set up in different localities. A much needed television program, Islam in Focus, was also organized. Also formed was a broad-based Muslim committee to present proposals on constitutional reforms to the government, and a special scouting wing for Muslim youths (boys and girls) called the Muslim Youth Brigade.

One of the most significant developments has been the building of an ‘interest-free’ Muslim Credit Union (MCU). With the efforts of a few dedicated brothers and sisters, the mcu, having governmental sanction, has become the first successful alternative to riba-based in stitutions in the region. At a period in which the economies of Trinidad and Tobago are on the decline, the MCU has been experiencing a spectacular growth much to the envy of other credit unions. Research is underway to establish an Islamic bank in the region. Attempts have also been made to establish similar institutions in Barbados and, hopefully, Guyana.

The need for individuals qualified in higher Islamic learning has always been pressing and urgent. To alleviate this, a number of workers were sent on scholarships to Saudi Arabia, Pakistan and India. Many of them returned in the ’80s and have since been helping to bring up the level of Islamic education in various communities. Indigenous efforts to create a viable institution for higher learning were born out of the two special one-year Islamic courses conducted in Guyana from 1980-83.

The Guyana Islamic Trust (GIT) has begun offering four-year programs in recitation, memorization and tafseer of the Qur’an, Hadith, Fiqh, biography of the Prophet (peace be upon him) and his companions; Islamic history, Arabic language, comparative religion,methodology of da’wah, modern Islamic movements and International affairs. The first batch will be graduating next year, insha’Allah.

The other communities have also seen a sustained growth and maturity. The Islamic Mission in Belize has been able to complete an Islamic Center with a full-fledged Islamic Elementary School, the only one in the region with an ongoing Islamic Curriculum. Presently the school has over 175 Muslim and non-Muslim students with full recognition by the Belizian Government. The Islamic Council of Jamaica has established a much-needed Islamic Center in Kingston, the capital, and has spread into the countryside by forming four subcenters, taking da’wah to the masses.

The Islamic Teaching Center in Barbados has undertaken plans to construct an adequate Islamic center. In addition to consistent lecture programs at the University of the West Indies (Cavehill campus), it has embarked on a regular weekly column in the daily newspapers and regular da’wah outreach programs to non Muslims.

The Jama’at-ul-Islam in Bahamas has been able to maintain a respectable profile in the ‘eyes’ of the society because of its attack on corruption immorality and drug problem. The communities in Grenada, Dominica, St. Vin cent, St. Lucia, Barmuda, Guadaloupe, and Martinique are in a formative stage of reorganizing and sustaining their communities.

In Trinidad, there have been two other noteworthy developments. First, the attempt by Jama’at-ul-Muslimeen, led by Yasin Abu Bakr, to apply the teachings of Islam to combat social problems in the country. This approach has had a very dramatic impact in motivating many African and other youths to return to Islam. In the past year, 60 to 70 people have entered Islam per week. At present, this rate of return to Islam has been on the decline but still remains impressive as compared with many other parts of the world. Unfortunately, the Jama’at-ul-Muslimeen has not been able to adequately provide education and training to all these ‘returnees.’ Many are slowly drifting away again. The IDM has been trying to offer classes to some of these.

There have also been claims that a few are involved in drugs and petty crimes but this still has to be substantiated. In July 1989, the Jama’at-ul-Muslimeen hosted a conference organized by the Islamic Call Society of Libya. It has also been reported that a number of key members left for two months ‘training’ in Libya. These disturbing events and the at titude of the leadership to maintain a posture of confrontation with the government has left the Jama’at-ul-Muslimeen in a difficult position.

The other contribution is the formation of the Darul-Uloom by Mufti Shahid, an Indian educated Islamic scholar. The Darul-Uloom has quite successfully established a Qur’anic school for children.

The ’80s have surely been a decade of stability and community development. They have provided the basis on which the challenges of the nineties can be tackled.

Attempts have also been made by Muslims in Suriname, Brazil, St. Croix, St. Thomas, Puerto Rico, Panama, Costa Rica, and Colombia to establish strong communities. These small but significant steps to establish a Muslim presence herald a unique future for Islam in this part of the world. Muslims in other parts can benefit tremendously from this experience of starting communities from scratch.

Challenges in the Nineties

The new decade will most likely see Islam influencing the lives of Caribbean people in an even greater way. Islam’s impact and resurgence has been watched and awaited by the local churches and governments. The Iranian revolution, the intifada and the Salman Rushdie affair have made Islam a spectacle that is grudgingly admired but still very much feared. For Muslims in the Caribbean, international events have had both a negative and positive backlash that still needs to be properly understood. It is now necessary for Muslims in the region to rise above these images of Islam and accept the responsibility of shaping the destiny of Islam with the help of Allah. No longer should Islam be an incidental entity, but must now become an acceptable and relevant force for building the Caribbean societies. Of course, this cannot be achieved without reflection on our strengths and weaknesses. The following are a few of the many challenges that must be successfully met by the Muslim community.

Community Development

The community life must be emphasized. In the eighties, we saw an emphasis on educational programs. In the new decade, we must transfer this into meaningful community life.

Communities must be established and strengthened so as to successfully face the pressures of the un-Islamic society. We must go back to the early days of the Prophet (pbuh) in Medina and note how a community of believers was built by emphasis on the Pard (obligatory acts), and the defining of relationships both within and outside of the community.

The concept of specific responsibility, leadership, shura and adherence to the Shari’a has to be explored and instituted in a way that is conducive to positive growth and submission to Allah. This inner dimension of tarbiyah (character molding and training) must be nurtured with love, mercy and compassion. It cannot be enforced (as shown by the experiments in Muslim countries today), but the believers must understand and desire wholeheartedly to serve the cause of Allah. This process must be gradual and tempered with hikmah (wisdom) so as to attract and util ize the human potentials in the Caribbean societies. The concept of brotherhood of Mus lims and of all human beings is a key to meaningful relationship. The underlying currents of racism in our societies must be neutralized as it has always proven to be divisive and destructive. A brotherhood that reflects sharing, concern and reaching out has to be manifested to build on our natural friendliness and hospitality as Caribbean people. It is only this way that the problems of poverty, drug addiction and the breaking-up of fraternities emanating from the encroaching materialism can be defeated.

A community life provides the practical growth of Islam and lays the foundation for a sustained and meaningful presence in the Caribbean. Our contribution has to be in building creative and liberated societies in which a sense of identity, purpose and commitment is achieved by our peoples. We need to realize that we have a valid contribution to make to the rest of mankind after our very uni que historical experience.

Relevance

The second challenge facing Muslim communities is how to make Islam relevant to the Caribbean environment. Not much has been done in this area. First, the Islamic literature from which our understandings are fashioned are imported from Pakistan, India and the Middle East and very recently from North America. Unfortunately, these literatures do not reflect our unique historical context, our amalgamated Western/Christian societies and the sociopolitical environment. With the experience of da’wah in the last two decades, a research unit must be established to devise a plan of action and to prepare literature to sensitize the people about Islam and its ongoing contribution to the region. The propagation of Islam is dependent on this project.

Our scholars were educated in different parts of the Muslim world and as such have brought the often divergent views on the Shari’a and how it should be approached. There is a need for the formation of a council of guidance comprising our ‘foreign trained’ scholars, qualified workers and trained specialists in the social sciences. Their task would be to identify issues, do relevant research, and make rulings by going to the original sources – the Qur’an and the Sunnah. The principle of Ijtehad has to be utilized in order to be relevant to the issues confronting us.

Social, economic and political problems abound in the Caribbean. How far should Muslims go in tackling those problems? In what manner can we prioritize these problems? To what extent should we identify with attempts to alleviate them? How much human and other resources should be channeled in combating them? How can we define our relationship with other groups and organizations confronting these issues without losing our sense of purpose and identity? These are a few of the many questions that have to be addressed in the ’90s.

Islamic Culture

The Caribbean has been a region of cultural domination with a resultant identity crisis. The European dominance and an infusion of ‘Americanism’ has stripped the indigenous people of .a sense of identity and defined values. This crisis has also affected Muslims and in fact has been compounded by the transposing of cultural strappings from India and Pakistan and most recently from the Mid dle East and the Africa. This has created a situation wherein Muslims are perceived as not only different but an alien people in the Caribbean society. ‘Local’ scholars and ‘foreign’ visitors have been guilty of imposing, in many cases unintentionally, these cultural strappings as Islamic culture.

Culture, not limited to dress, but in particular focusing on the family life, the upbringing of children and alternative cultural activities in the communities has to be encouraged. Steps taken by the GIT in this regard are highly commendable but they need to be expanded to other communities. Family life and children need to be prioritized as they provide the bases for community development.

Economic Dilemma

The reality of the economic situation in the region is grim with the threat of poverty loom ing on the horizons. More and more countries are beginning to face a debt crisis, some are on the poverty level and others barely surviving. The dependence on foreign capital and markets has created an economic enslavement. Muslims, especially in the newly emerging communities, cannot escape this predicament. It is a fact that much more would have been achieved in the ’80s if Muslims were better organized economically. An example of this would have been an expansion of the Guyana Islamic Institute as a regional institution.

One of the bright example is the Muslim Credit Union in Trinidad. The research towards establishing an Islamic Bank in the region by MCU is crucial in creating capital for investments in the region. But these impor tant pioneering efforts will take time and can yield good results only in countries like Guyana, Trinidad and Tobago, which have large Muslim populations.

In the numerous smaller communities other strategies have to be developed. The principle of self-reliance that emerged in the ’80s must be pursued into the ’90s. Much thought and discussion is needed to ensure that this vital area is properly developed. The following are a few recommendations:

(a) Communities pool their savings, set up a financial entity and initiate small projects that can sustain the community. Care must be taken that qualified people are consulted, projects are viable and serious Muslims are employed. Projects that provide for the needs of the community (e.g., hala! foods) should be started.

(b) Feasibility studies in selected projects should be properly prepared and documented. Attempts should be made to solicit capital from wealthy Muslims in the region or from

the growing number of Muslim investment houses mushrooming in the U.S. such as Muslim Savings and Investments (MSI), California and Bait-ul-Maal (BMI), New Jersey.. The im portance of supporting struggling Muslim communities must be emphasized.

(c) The problem of Muslims migrating to ‘North’ for economic reasons has left many communities without the help, expertise and support that is very much needed. Local people who have lived in the United States and Canada and have established themselves should be encouraged to share their success and experience with their community back home. Trips back to the region should be organized and perhaps even a Muslim Tourist Bureau be formed. This would provide revenue and a stimulus to many communities. The Caribbean Muslim Support Group of North America (CMSG), formed in June 1988 in New York, can play a crucial role in bridging this gap. The CMSG presently has contact with Caribbean Muslims in New York, Miami, Chicago, Los Angeles, Baltimore, Toronto and Vancouver, and with members from a variety of countries, Belize, Jamaica, Bar bados, Trinidad, St. Kitts, Haiti, Surinam, Costa Rica and Guyana.

Propagation and Da’wah

The challenge of taking the message of Islam to the people of the Caribbean still needs to be addressed. Over the years, there have been a number of attempts to deal with this but by and large this has remained an individual effort. The only recognizable attempt at detailed planning and organized programs has been the Association of Islamic Communities of the Caribbean and Latin America and, in particular, its member-bodies, the GIT and the Islamic Trust of Trinidad and Tobago (now called to the Islamic Da’wah Movement).

The Muslim community should also provide direction on how to deal with media propaganda that portrays Islam as an international threat. Not as a beneficial unifying force; to what extent Muslims should get involved in public issues such as corruption, drugs, AIDS etc.

The writer is secretary of the Caribbean Muslim Support Group in North America, and is based in New York City.